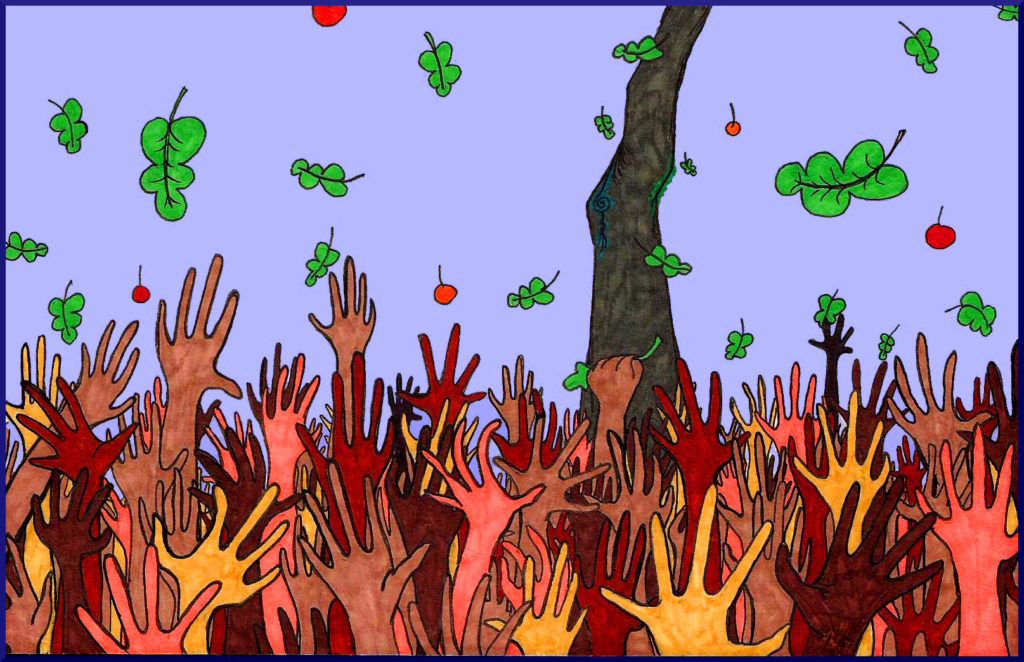

October 28th is the National Immigrants Day in the USA. To honor this day, here is a little article dedicated to immigrant children who grew up as “citizens of the world” in a world that still doesn’t know what to do with them.

Being a multicultural, multi-lingual individual should be considered its own ethnicity. We relate to each other not as much on the basis of national identity as on the basis of “being more than one thing”. As a Russian-American, for example, I have more in common with other hyphenated internationals than with just Russians or just Americans.

Because what unites multicultural individuals is hybridity. You know how ethnically homogeneous people are slaughtering each other over arbitrary religious differences, national boundaries and disparate belief systems and ideologies that, to them, seem “impossible” to overcome? Well, multicultural people manage to combine elements of these cultures within themselves and make them work! But, as with any project of the self, this journey comes with challenges that result in major triumphs and epic fails. Here are some examples of how being multicultural is, simultaneously, awesome and a huge pain in the ass.

Pro: Being multicultural means having diverse family and friends with cool, interesting traditions.

Con: All sides of your family as well as compatriots expect you to put in a 100% of yourself into maintaining your culture. For a multicultural individual that’s, like, 200-300%!!!

Being plugged into multiple worlds as an insider is a very fulfilling perk most multicultural peeps wouldn’t trade in for anything. Speaking numerous languages is useful and delightful. The inside jokes alone are too good to pass up. It only makes sense that having multiple perspectives from which to experience the world is more balanced, interesting and fun than having just one.

The downside is that family members will heap completely unrealistic and monopolizing demands for cultural knowledge, religious practices and ethnic loyalty on you. And they will not hesitate to mock and shame you cruelly and publicly, if you don’t live up to the traditional roles from the “old world” expected of you.

But then, you walk out of the house and you’re back in the USA! So, you put on your best version of “Americanness”, so that you don’t spook your conservative coworkers and random mall shoppers by being threateningly “too ethnic” for their homogeneous sensibilities.

As the result, you are constantly oscillating between shades of national identity for the benefit of others, which is exhausting and also confusing to one’s sense of self.

Pro: You have a wide circle of very diverse friends who are fun and worldly.

Con: You get to hear people from several different ethnicities be racist about each other.

When you are part of more than one cultural group, you get both, the benefits and the offenses of having “insider” access to hearing them talk among themselves. The upside is obvious: more diverse friends, more diverse fun.

The downside, quite frankly, is bigotry overload. You find yourself having to listen to more than one group of loudmouths say atrociously ignorant things about other races and ethnicities. Witnessing various circles of your friends and family gather and yak, you learn just how socially constructed ethnocentrism is. Each group of people claims to be special and different — but talks equally stupid smack about each other while exhibiting comparable levels of myopia about their own beliefs and practices. The bottom line is: you get tired of facepalming and feeling embarrassed for people you otherwise respect.

Pro: You are fluent in each of the cultures you represent and can speak with confidence about their respective histories, geographies and politics.

Con: You end up as the de facto “ambassador” for whichever side is least represented in a given debate.

Multicultural people make excellent diplomats because they are less easily seduced by overzealous nationalism. They know that there is nothing to gain and everything to lose in cultural conflict. They understand that cultural differences are best appreciated (and solved) through fusion not competition, unity not xenophobia.

The flip-side is the self-appointed social responsibility the multicultural individual feels to represent all sides fairly. There is a special dynamic that happens to such people when they take part in conversations / debates involving cross-cultural conflict. I run into this all the time: I criticize the U.S. to Americans but defend it to Russians — and vise versa — I tear Russia apart when I speak with Russians but defend the hell out of it when Americans get too stereotyp-y about it. To be clear: I stand with my opinions and principles no matter who I’m talking to. But the peacemaking pitfall is hard to resist: it feels like a duty to stand up for the party that is not here to defend itself. As the result, the multicultural individual can be perceived by each side as “always defending the other guy”, which can be socially isolating.

Pro: If you are multi-lingual, you get to enjoy literature, film, music and humor on multiple cross-levels of comprehension, which is a very rewarding experience.

Con: You are called upon to translate everything, all the time by non-English-speaking family members.

The advantages of multi-lingualism are many. Even before all the scientific publications came out on the subject, every multi-lingual person already knew that speaking more than one language fluently is a cognitive advantage that will enhance the hell out of your intelligence, your inspiration, your social skills, your professional options and, yes, your love life.

But if you grew up as a child in a recently-immigrated family, you also know the struggle of being involuntarily put in charge of every kind of communication thrown at your family: from screening emails for scams to filling out tax documents to handling the Jehovah’s Witnesses at the door to making sense of the dreaded letters from Immigration. By now, studies have shown that the whole “eternally-on-call-translator” gig forced by immigrant families on their younger members actually puts too much pressure to the already existing stress of cultural assimilation and the growing pains of childhood / adolescence. In other words, being your family’s 24/7 translator is strenuous AF when you’re still learning the language yourself and trying to carve out a place under the sun at the school cafeteria.

Oh, and once cast as the family translator, you stay the family translator well past growing up! My Mom used to call me at all hours of day and night with translation questions that would completely throw me off my game due to their randomness. Even nowadays, when Googling a word takes significantly less time than picking up the phone, Mom inevitably ambushes me with language questions when I least expect them. Isolated words or snippets of phrases that make no sense without context render me an instant idiot. Suddenly, the translation for “…her first-born porcupine was very…” is the farthest thing from my mind and, the more I search my vocabulary, the more blanks I draw.

Mind you, Mom also goes into a linguistic stupor around me. She has been teaching science at an American college for two decades — but I come around and, suddenly, it’s like she got off the boat yesterday, wide-eyed and disoriented. It is as if, when I am around, her brain refuses to process the English language and I’m the court-appointed interpreter that is now doing all the talking on her behalf. It drives me bonkers, but I also sympathize because I think it is some form of PTSD from having to learn a brand new language and adjust to a completely different world as a middle-aged refugee.

Pro: Being from more than one place, you can conveniently “wear” one national identity over another, depending on the politics and sympathies of a given social environment.

Con: People will selectively attribute you different national characteristics, depending on how it serves their argument.

That question: “Where are you from?” — what a conundrum for multi-cultural people! I’m from all over the place, ok??? Unfortunately, most people are not satisfied with that answer. But then again, most people aren’t actually prepared to hear your complicated life story where you painstakingly explain each cultural influence that made you the person you are today. More often than not, you end up having to simplify your cultural identity for people by naming just one. But that’s trickier than it sounds too!

Sometimes you are at a place where your national origins can provoke a variety of unwanted reactions that can range from ugly sneers to getting your ass beat or murdered. Multicultural individuals have the advantage of choosing which national identity to reveal and which to suppress, depending on the geopolitical climate around them.

When visiting foreign countries, depending on the current attitude toward the USA and Russia, I get to pick which is the more benign national identity to display in order to have the smoothest ride. For instance, when I travel in Europe, being an American fits me best because it’s a “safe” nationality to be. When I’m in South America, I stress the living bejeebus out of being a Ruski. Because in countries that aren’t terribly thrilled with the history of European / North American colonialism in their regions, it is less obnoxious to be a mysterious, hard-core, edgy Russian, as opposed to an imperialist American swine. In other places, like Turkey or some parts of India, where Russian tourists wreak havoc on local resorts, I avoid mentioning my Russian-ness, lest I get grouped with the bleached canaries and bloated meat-necks that have come to represent “my kind” in those parts.

Let me just clarify that I don’t generally hide my multi-national origins as some manipulative tactic to get ahead — or for the sheer lulz of it. Denying who you are does violence unto the self, so it’s best avoided. It’s just that there are times when this “passing” as one nationality over another is a matter of safety. As in: not attracting the wrong attention, not getting drawn into a painful political squabble where you are expected to represent this or that side, not getting your ass kicked by drunk “patriots”, etc. Sadly, the few times I had to buckle down and straight-up obscure my origins was around Russians who I knew for sure would turn hostile instead of accepting me “as is”.

As a multicultural person, you live with the awareness that sometimes “your own people” are your biggest threat. Because when it comes to nations with homogeneous prescriptions for “what a standard citizen should be“, people can be suspicious and hostile towards those who claim to be one of their own — but look, sound, or act differently than expected. Visiting Russia as a Soviet-era immigrant also comes with the honor of being seen as a traitorous “enemy of the people” who betrayed their “motherland” for the green pastures of soulless capitalism.

As such, I’ve had my fill of being treated like garbage on my visits to Russia when I earnestly tried to fit in as a Russian. So, in the desperate attempt to shield myself from aggression, I started telling people I was American. Lo and behold, everyone became nice and welcoming. Under the magical cloak of Americanness, all the traits that made me an abnormal-acting Russian suddenly became adorable eccentricities of a charming foreigner. Comments such as “You talk funny, are you mentally ill?” were replaced with “Your Russian is fantastic!” Most importantly, everyone got off my back about how to live my life. When I went as “Russian”, even the healthy parts of my lifestyle were scrutinized as weird or “wrong”, whereas, as an “American”, even my bad habits were seen as a mark of classy sophistication. The mystery of “the stranger” has this seductive effect on people, that’s just how it is. As a multicultural person, I appreciate having the opportunity to camouflage myself as “us” or “them”, depending on what’s safer.

But the cultural camouflage only works with strangers — not people who already know you. And that’s where the most damage comes from, honestly. When people know that you are a “half-something”, the familiarity and negligence with which your opinions are met can be down-right degrading. This is a battle you can’t win as a multicultural person: your mono-cultural compatriots can liberally swing between dismissing your point of view “because you’re just one of us yokels, so what do you know?” and discrediting your point of view “because you’re not one of us sophisticated people, so what do you know?”

Pro: You feel like you belong everywhere.

Con: You feel like you don’t belong anywhere.

This is a duality that haunts all multicultural citizens of Planet Earth. Most people of the world grew up in one place with a fairly singular sense of national identity that gives them a sense of belonging, direction and security, as well as rootedness in the land and its history and traditions.

Multicultural individuals, on the other hand, either feel their “roots” in more than one place — or don’t feel “grounded” anyplace at all. We feel “at home” in the world in general, but have a hard time feeling like we belong “all the way” somewhere in particular. As mentioned, many of us were outright rejected by our homelands and the people in them. And then, our adoptive countries put us through some harsh hazing before we felt like we fit in. Once you chill out a little bit and begin to get this whole cultural assimilation thing down, you are still reminded that you are “not from here” by people who might not even be able to point out “here” on the map.

I immigrated to the States at a young enough age that, once I got a grip on the language fluency, I got to feel pretty “American” for a while there (a privilege bestowed only on white immigrants, btw, while native-born Americans of color still get asked “where they’re from” on the regular…) But the current climate of anti-immigrant hatred has me feeling on edge, to put it mildly. As a political refugee from the USSR, you always carry paranoia that a dark van will come to take you away in the middle of the night — that’s just childhood trauma that’s been wired in there for good. But, today, that’s more than just paranoia — it’s a real possibility for so many people in the USA. And I’ll tell you, it is not fear I feel — it’s bitter, crushing disappointment. It’s like finding out that your adoptive parents are just as abusive and immature as the ones that gave you up. You begin to suspect that, even though the paperwork had gone through, this isn’t your “forever home” after all. And you just think to yourself: where can I run to next?

My solution has been to travel extensively and live abroad as much as possible, struggling with new languages, learning new cultural ways of life, trudging through new bureaucracies. After a lifetime of doing this, it has occurred to me that I compulsively seek out these experiences because being the stranger in a strange land is my only option, the only status that makes sense. I can’t fit in as a “native” anywhere, but I thrive as a foreigner because it feels normal and natural and is, basically, all I know.

It’s complicated and tumultuous being a person that hosts cultural multitudes within themselves. You have to constantly reconcile your internal contradictions; you have to be different things to different people; you are perpetually heartbroken over the social tensions between the different groups you belong to — and you are horrified and disgusted by petty geopolitics in general.

But I would not have myself any other way. Because, despite the heavy price of rootlessness and perpetual social “othering”, the precious big picture perspective is absolutely worth it. So what if no one nation of people claims me as their own? The world, in its unfathomable hugeness, is truly my oyster, my playground. Because I, along with my fellow multicultural wanderers, know the ultimate secret to human belonging. Properties, societies, national boundaries — they all come and go — but if you know who you are, you are already home.